Bayan Lepas-Teluk Kumbar Flyover during construction. (6 January, 2017)

Bayan Lepas-Teluk Kumbar Flyover during construction. (6 January, 2017)

The sensible approach to preservation should not be one of blind adherence to rigid rules, but one that carefully evaluates needs and circumstances.

By Timothy Tye

When I was small, there was a good nasi kandar stall in the Bayan Lepas old town. My Dad used to take me there, and every time, I would ask for "tambah nasi". The nasi kandar stall occupied a rickety one-storey coffee shop along the Bayan Lepas Main Road. On that same row were a few other single- and double-storey shophouses, including a beautiful double-storey prewar townhouse.

If you wish to visit that nasi kandar, you couldn't. It was gone many, many years ago. But that townhouse was only demolished quite recently. I do wish that building could be preserved, but I also understand that it is a necessary sacrifice. If it were in George Town, within sight of local NGOs, they would surely have made a lot of noise. In this case, it escaped their attention, and perhaps for the better.

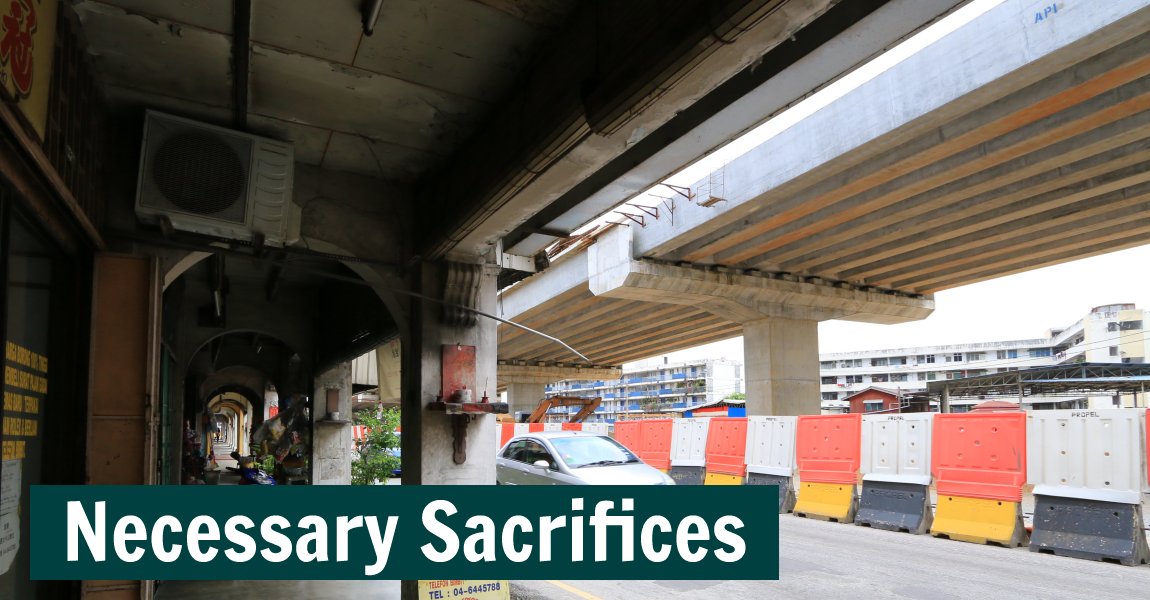

The townhouse, and the rest of the shophouses on the south side of Jalan Bayan Lepas, was in the path of the Bayan Lepas-Teluk Kumbar Flyover. Due to the rapid development in Teluk Kumbar and Balik Pulau, the volume of traffic from Jalan Teluk Kumbar heading towards Jalan Bayan Lepas had increased exponentially, creating a huge bottleneck at the junction of Jalan Permatang Damar Laut. Before the flyover was completed, it was not unusual to be stuck at that junction for 45 minutes or more.

The townhouse that was demolished. (12 July, 2008)

The townhouse that was demolished. (12 July, 2008)

Nowadays motorists - including people who pride themselves to be very heritage conscious - get a smooth drive through Bayan Lepas town towards Teluk Kumbar, unaware of the sacrifice necessary to make that possible. The people of Teluk Kumbar, Gertak Sanggul and Balik Pulau can now enjoy better connectivity thanks to our willingness to make that sacrifice. But were we lucky there? If word of that pre-war townhouse reached the ears of the NGOs early, would they have protested its demolition, thereby denying the people of Teluk Kumbar, Gertak Sanggul and Balik Pulau an opportunity for better connectivity?

Traffic was at a crawl towards along Jalan Teluk Kumbar, before and during construction of the flyover. (29 November, 2014)

Traffic was at a crawl towards along Jalan Teluk Kumbar, before and during construction of the flyover. (29 November, 2014)

What wisdom is there to apply a blanket ban on demolition of buildings that have surpassed a certain age? Do we preserve a building just because it is old? And why are we preoccupied with buildings, why not other stuff?

After eating fish, do you keep the fishbone? Well, unless you happen to be eating a particularly peculiar or expensive fish - a fugu perhaps - it is unlikely you would want to keep an ordinary fishbone. Because it has no value?

What if I were to tell you, that right this minute, an archaeologist somewhere is holding a celebration. After removing tons of rubble from an ancient archaeological site, he uncovered what appeared to be the refuse pit of a thousand-year-old abode, and there, discovered a bowl with some charred grains and a fishbone? A fishbone unceremoniously discarded a thousand years ago offers him insights into the diet of that ancient civilisation. Something of no value to you could be of great value to someone else in the future.

So, should you start keeping all your fishbones, for the sake of a future archaeologist a thousand years from now? And while you are at it, remember not to wash the fishbones - you wouldn't want to deny him the chance to discover what spices you used in cooking. Your house will be well known throughout your neighbourhood, and possibly all over Penang, as The House That Smells Fishy.

Of course I am being completely ridiculous! And I do so to prove a point.

We don't retain something of no value to us for the sake of someone else far in the future. It's the people of the present that matters most. But the question challenging us is: what do we preserve and of that we intend to discard, do we have the will (and guts) to do it?

Pay a visit to any block of flats in a rundown neighbourhood, and you are quite likely to come upon a house quite different from the rest: the owner doesn't throw anything away. He has stuff cluttering his whole living space and spilling into the corridor outside. There are stacks of old newspapers, broken toys, broken furniture, television sets and computer monitors. Nothing is working and everything is collecting dust. That's because the owner could not bring himself to throw anything away, and on top of that, he regularly rummages garbage bins for things to salvage. Everything is too sayang. In so doing, he reduces his human habitat into a rathole.

The main problem with trying to save everything is that, space is finite. Whether you live in a 500 sq ft flat, or a 5,000 sq ft super condo, if you keep everything, every fishbone from every meal, every chocolate wrapper, every plastic wrap, for the sake of a future archaeologist, pretty soon you would be buried in your own clutter. Every time you clean your cupboard, you discover stuff that you bought a decade ago, but never got to use, because it was buried out of sight.

Now take the home metaphor and apply it to a city. The same logic applies. We can attempt to reclaim some land, but on the whole, space is finite. There just isn't enough space for a city to grow if it keeps all its old building, for no other reason than because it is old. But how do we decide what to keep and what to demolish?

Easy: if it's fugu fishbone you keep, if it's not you throw away.

Every plot of land, though built over once before, should be given a chance to be redeveloped, if the redevelopment serves a better purpose. To demolish what is old takes the same level of courage as to throw away something you have owned for years but never use, and you badly need more space in your house.

But when do we preserve?

If a building has particular significance, then there's good reason to preserve it. Take Fort Cornwallis. The history of Penang is attached to it, so of course we would want to preserve it. If a historical event has taken place there, or a historical person had stayed there, those are all reasons we want to keep a building.

What if there is nothing special that has happened at the building, and its only merit is its age? That should not be the reason for preservation, especially if there are many other similar buildings. If a building has been left in ruins for a long time, we should find out why so. What if it was abandoned because unpleasant incidents had taken place there, or scary things have been seen there, would we be eager to preserve it still?

When it comes to grading old buildings, I believe we follow the practice of the United Kingdom. How much we adopt of the UK practice, I do not know. But I believe we grade listed buildings as follows, based on paper presented by Dr A. Ghafar Ahmad of Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru:

First, we look at what they do in the United Kingdom. For the purpose of statutory protection, listed buildings in the UK are classified into two grades which are:

Definition of the Gradings (UK)1 (ref)

Grade I Buildings of outstanding national interest which only the greatest necessity would justify their demolition.Grade II Buildings of special architectural or historic interest which have a good claim to survival.

What seems apparent in the above definition is that being categorized as Grade I does not save a building from demolition, if the greatest necessity can be demonstrated to justify the action. It only means that Grade I buildings have a greater chance to avoid being demolished than Grade II. Both grades of building are according specific degrees of protection but both can be demolished. Again, this is for the United Kingdom. Based on that system, a 3-tier grading system was established for Malaysia as follows:

Definition of the Gradings (Malaysia)

Grade I Buildings of architectural excellence and historical importance. It is essential to the national interest that they may be preserved. (Examples: the Railway Station and Administrative Buildings, Selangor Club, Sultan Abdul Samad Building and Jamek Mosque in Kuala Lumpur; Porta de Santiago, St. Paul's Church, Stadhuys Building and Christ Church in Malacca)Grade II Buildings of architectural and historical interest and value to the state. Examples: the Johore Royal Museum in Johor Bahru and Penang Court Building in George Town).

Grade III Buildings of special characters architecturally or historically which may have a good claim for survival. Such building are of either religious, cultural, social interest or be examples of a particular culture and craftsmanship.

What I note here is that the grading does not specify that a building cannot be demolished. It only mentions the various degrees of heritage significance of buildings, to which we apply corresponding protection. What is clear here is that to achieve Grade I, a building must be of national interest. For Grade II, it needs to exhibit architectural or historical interest. That means, it has to exhibit specific elements.

Who is it to judge that a building is Grade I, II or III? Is this not open to personal interpretation, leading towards unjustified categorization of buildings? If the person sent to categorize buildings has a zeal for protection, would he or she be more likely to categorize a building that is otherwise Grade III to Grades I or II? Another appraiser who is more liberal might apply a Grade III status to a Grade II building.

I am keen to ensure that every old building with heritage or architectural merit has a chance to be preserved. However, my priority is and has always been to put the welfare of the people first. If a city holds on to old buildings for the sake of doing that, it is like holding on to fishbones which should have been discarded. If demolishing will allow the land to be redeveloped in ways that will bring about skilled employment, or outstanding products and services, should we stand in the path of demolition?

Some oppose the redevelopment of a site for the construction of buildings catering to the rich, because they are not far sighted enough to see the benefit trickling down to the poor. For example, how would building a hospital for the rich helps the poor? What they do not see is that, in order for the government to have the means to increase its help for the poor, it first needs to create new sources of revenue. We cannot expect the government to keep on increasing the benefits for the poor, without allowing it avenues to generate more income. It is therefore in our own interest to help the government create sources of income for itself, for then it will be channelled back to us.

This entire row of shophouses had to make way for the Bayan Lepas flyover. (12 July, 2008)

This entire row of shophouses had to make way for the Bayan Lepas flyover. (12 July, 2008)

When faced with the dilemma of whether to preserve or to demolish, how do we move forward? The sensible approach to preservation should not be one of blind adherence to rigid rules (in fact, are those rules or guidelines?), but one that carefully evaluates needs and circumstances. If circumstance dictates that the people fare better that the land be redeveloped, then it should. If redevelopment brings about no significant merit, then we preserve.

A decision by the city to demolish an old building is not one that can be done in haste, but after careful evaluation. Do we preserve the old shophouses in Bayan Lepas? As much as I want to preserve them, I am mindful that the flyover will enhance the quality of life for the people, especially those in Teluk Kumbar, Gertak Sanggul, Balik Pulau, people who are often mute to voice their hardship. Those of us who have the knowledge of people's hardship should do the right thing for the people.

For the same reason that we do not keep every fishbone from our meals for the sake of future archaeologists, so neither should we keep every old building just because it is old. We need to strike a balance, and if what we do improves lives, we need the guts to make necessary sacrifices.

About the author

Timothy Tye is a spokesperson for AnakPinang. He authors Penang Travel Tips and served for three terms (2005-2011) as Council Member of Penang Heritage Trust. He promotes the preservation of Penang's culture and tangible, intangible and built heritage, while voicing the need to strike a fair balance between preservation and re-development.References

- From Spot Listing to Grading - Heritage Buildings: The U.K. Experience, by Dr. A. Ghafar Ahmad, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (1995)

Further Reading

Copyright © 2018-2021 AnakPinang. All Rights Reserved.